Coronavirus reinfections are real but very, very rare

Содержание:

- Does recovering from COVID-19 make you immune?

- What you can do

- Coronavirus Risk Factors

- Coronavirus Vaccine

- Coronavirus Diagnosis

- Similar articles

- What research has there been on this subject?

- COVID-19 may be a vascular disease more than a respiratory one

- Can you get re-infected after recovering from COVID-19?

- Abstract

- Where new cases are higher and staying high

- Where new cases are higher but going down

- Where new cases are lower but going up

- What Is COVID-19?

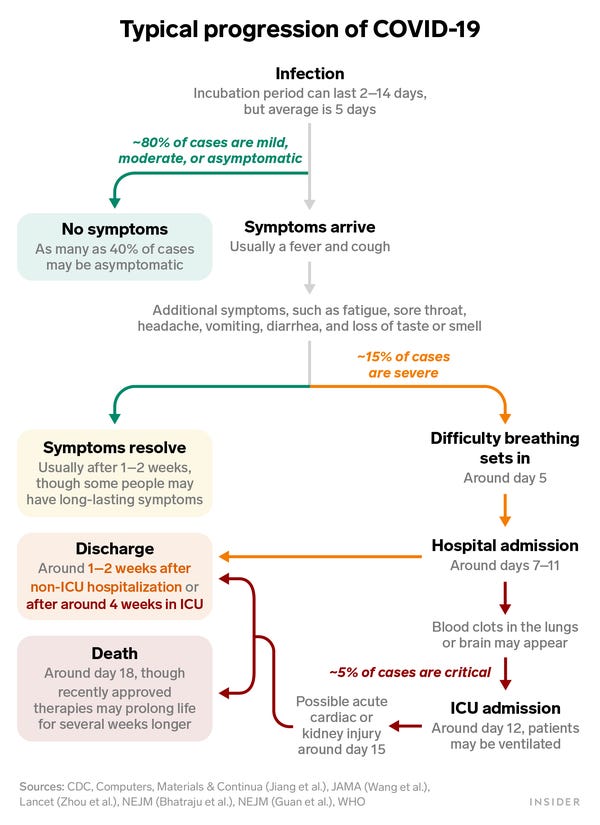

- A day-by-day breakdown

- Coronavirus Transmission

- Can the virus be ‘reactivated’ after you recover?

- United States

- Past Coronaviruses

- The most concerning symptom: shortness of breath

- Cited by 339 articles

Does recovering from COVID-19 make you immune?

There hasn’t been enough time to research COVID-19 in order to determine whether patients who recover from COVID-19 are immune to the disease—and if so, how long the immunity will last. However, preliminary studies provide some clues. For example, one study conducted by Chinese researchers (which has not yet been peer-reviewed) found that antibodies in rhesus monkeys kept primates that had recovered from COVID-19 from becoming infected again upon exposure to the virus.

In the absence of more information, researchers have been looking at what is known about other members of the coronavirus family. “We are only three and a half months into the pandemic,” Hsu Li Yang, an associate professor and infectious disease expert at the National University of Singapore, says. “The comments we’re making are based on previous knowledge of other human coronavirus and SARS. But whether they extrapolate across COVID-19, we’re not so sure at present.”

One study conducted by Taiwanese researchers found that survivors of the SARS outbreak in 2003 had antibodies that lasted for up to three years—suggesting immunity. Hui notes that survivors of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS, which is also caused by a virus related to the one that causes COVID-19) were found to last just around a year.

Menachery estimates that COVID-19 antibodies will remain in a patient’s system for “two to three years,” based on what’s known about other coronaviruses, but he says it’s too early to know for certain. The degree of immunity could also differ from person to person depending on the strength of the patient’s antibody response. Younger, healthier people will likely generate a more robust antibody response, giving them more protection against the virus in future.

“We would expect that if you have antibodies that neutralize the virus, you will have immunity,” Menachery says. “How long the antibodies last is still in question.”

Please send tips, leads, and stories from the frontlines to virus@time.com.

Most Popular on TIME

1

1996: Ruth Bader Ginsburg

2

1938: Frida Kahlo

3

1971: Angela Davis

Write to Hillary Leung at hillary.leung@time.com.

What you can do

Experts’ understanding of how the Covid-19 works is growing. It seems that there are four factors that most likely play a role: how close you get to an infected person; how long you are near that person; whether that person expels viral droplets on or near you; and how much you touch your face afterwards. Here is a guide to the symptoms of Covid-19.

You can help reduce your risk and do your part to protect others by following some basic steps:

Keep your distance from others. Stay at least six feet away from people outside your household as much as possible.

Wear a mask outside your home. A mask protects others from your germs, and it protects you from infection as well. The more people who wear masks, the more we all stay safer.

Wash your hands often. Anytime you come in contact with a surface outside your home, scrub with soap for at least 20 seconds, rinse and then dry your hands with a clean towel.

Avoid touching your face. The virus can spread when our hands come into contact with the virus, and we touch our nose, mouth or eyes. Try to keep your hands away from your face unless you have just recently washed them.

Here’s a complete guide on how you can prepare for the coronavirus outbreak.

Anyone can get COVID-19, and most infections are mild. The older you are, the higher your risk of severe illness.

You also a have higher chance of serious illness if you have one of these health conditions:

- Chronic kidney disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- A weakened immune system because of an organ transplant

- Obesity

- Serious heart conditions such as heart failure or coronary artery disease

- Sickle cell disease

- Type 2 diabetes

Conditions that could lead to severe COVID-19 illness include:

- Moderate to severe asthma

- Diseases that affect your blood vessels and blood flow to your brain

- Cystic fibrosis

- High blood pressure

- A weakened immune system because of a blood or bone marrow transplant, HIV, or medications like corticosteroids

- Dementia

- Liver disease

- Pregnancy

- Damaged or scarred lung tissue (pulmonary fibrosis)

- Smoking

- Thalassemia

- Type 1 diabetes

On December 11, 2020, the Food and Drug Administration granted emergency authorization use in the U.S. of the Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for those 16 years of age and older. Within a week, Moderna was also granted an EAU in the U.S.. Both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines require two doses, administered a few weeks apart.

Priority allocation of the doses has been given to health care workers and the elderly. It is estimated that it will be spring or summer before the general public will have acess to the vaccines. There are still unanswered questions regarding their safety in pregnant women.

Call your doctor or local health department if you think you’ve been exposed and have symptoms like:

- Fever of 100 F or higher

- Cough

- Trouble breathing

In most states, testing facilities have become more readily available. While some require an appointment, others are simply drive-up..

A swab test is the most common method. It looks for signs of the virus in your upper respiratory tract. The person giving the test puts a swab up your nose to get a sample from the back of your nose and throat. That sample usually goes to a lab that looks for viral material, but some areas may have rapid tests that give results in as little as 15 minutes.

If there are signs of the virus, the test is positive. A negative test could mean there is no virus or there wasn’t enough to measure. That can happen early in an infection. It usually takes 24 hours to get results, but the tests must be collected, stored, shipped to a lab, and processed.

Similar articles

-

Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology.

Channappanavar R, Perlman S.

Channappanavar R, et al.

Semin Immunopathol. 2017 Jul;39(5):529-539. doi: 10.1007/s00281-017-0629-x. Epub 2017 May 2.

Semin Immunopathol. 2017.PMID: 28466096

Free PMC article.Review.

-

Molecular Basis of Coronavirus Virulence and Vaccine Development.

Enjuanes L, Zuñiga S, Castaño-Rodriguez C, Gutierrez-Alvarez J, Canton J, Sola I.

Enjuanes L, et al.

Adv Virus Res. 2016;96:245-286. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2016.08.003. Epub 2016 Aug 30.

Adv Virus Res. 2016.PMID: 27712626

Free PMC article.Review.

-

A molecular arms race between host innate antiviral response and emerging human coronaviruses.

Wong LY, Lui PY, Jin DY.

Wong LY, et al.

Virol Sin. 2016 Feb;31(1):12-23. doi: 10.1007/s12250-015-3683-3. Epub 2016 Jan 15.

Virol Sin. 2016.PMID: 26786772

Free PMC article.Review.

-

Innate and adaptive immune responses against coronavirus.

Hosseini A, Hashemi V, Shomali N, Asghari F, Gharibi T, Akbari M, Gholizadeh S, Jafari A.

Hosseini A, et al.

Biomed Pharmacother. 2020 Dec;132:110859. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110859. Epub 2020 Oct 22.

Biomed Pharmacother. 2020.PMID: 33120236

Free PMC article.Review.

-

Primary severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection limits replication but not lung inflammation upon homologous rechallenge.

Clay C, Donart N, Fomukong N, Knight JB, Lei W, Price L, Hahn F, Van Westrienen J, Harrod KS.

Clay C, et al.

J Virol. 2012 Apr;86(8):4234-44. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06791-11. Epub 2012 Feb 15.

J Virol. 2012.PMID: 22345460

Free PMC article.

What research has there been on this subject?

A study on recovered COVID-19 patients in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen found that 38 out of 262, or almost 15% of the patients, tested positive after they were discharged. They were confirmed via PCR (polymerase chain reaction) tests, currently the gold standard for coronavirus testing. The study has yet to be peer reviewed, but offers some early insight into the potential for re-infection. The 38 patients were mostly young (below the age of 14) and displayed mild symptoms during their period of infection. The patients generally were not symptomatic at the time of their second positive test.

In Wuhan, China, where the pandemic began, researchers looked at a case study of four medical workers who had three consecutive positive PCR tests after having seemingly recovered. Similar to the study in Shenzhen, the patients were asymptomatic and their family members were not infected.

COVID-19 may be a vascular disease more than a respiratory one

Though the coronavirus attacks the lungs first, it can infect the heart, kidneys, liver, brain, and intestines as well. Some research has suggested that COVID-19 is a vascular disease instead of a respiratory one, meaning it can travel through the blood vessels. This is the reason for additional complications like heart damage or stroke.

Scientists have a few theories about why some coronavirus patients take a rapid turn for the worse. One is that immune systems overreact by producing a «cytokine storm» — a release of chemical signals that instruct the body to attack its own cells.

Dr. Panagis Galiatsatos, a pulmonary physician at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, compared that process to an earthquake — generally, it’s the falling buildings that kill someone, not the quake itself.

«Your infection is a rattling of your immune system,» he said. «If your immune system is just not well structured, it’s just going to collapse.»

Can you get re-infected after recovering from COVID-19?

There remains a lot of uncertainty, but experts TIME spoke with say that it’s likely the reports of patients who seemed to have recovered but then tested positive again were not examples of re-infection, but were cases where lingering infection was not detected by tests for a period of time.

Experts say the body’s antibody response, triggered by the onset of a virus, means it is unlikely that patients who have recovered from COVID-19 can get re-infected so soon after contracting the virus. Antibodies are normally produced in a patient’s body around seven to 10 days after the initial onset of a virus, says Vineet Menachery, a virologist at the University of Texas Medical Branch.

Instead, testing positive after recovery could just mean the tests resulted in a false negative and that the patient is still infected. “It may be because of the quality of the specimen that they took and may be because the test was not so sensitive,” explains David Hui, a respiratory medicine expert at the Chinese University of Hong Kong who also studied the 2002-2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which is caused by a coronavirus in the same family as SARS-CoV-2.

A positive test after recovery could also be detecting the residual viral RNA that has remained in the body, but not in high enough amounts to cause disease, says Menachery. “Viral RNA can last a long time even after the actual virus has been stopped.”

Abstract

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are by far the largest group of known positive-sense RNA viruses having an extensive range of natural hosts. In the past few decades, newly evolved Coronaviruses have posed a global threat to public health. The immune response is essential to control and eliminate CoV infections, however, maladjusted immune responses may result in immunopathology and impaired pulmonary gas exchange. Gaining a deeper understanding of the interaction between Coronaviruses and the innate immune systems of the hosts may shed light on the development and persistence of inflammation in the lungs and hopefully can reduce the risk of lung inflammation caused by CoVs. In this review, we provide an update on CoV infections and relevant diseases, particularly the host defense against CoV-induced inflammation of lung tissue, as well as the role of the innate immune system in the pathogenesis and clinical treatment.

Where new cases are higher and staying high

Countries where new cases are higher had a daily average of at least four new cases per 100,000 people over the past week. The charts, which are all on the same scale, show daily cases per capita and are of countries with at least five million people.

7-day average

Netherlands

Jan. 22

Dec. 22

Sweden

Czech Republic

United States

Denmark

Slovakia

Switzerland

U.K.

Israel

Portugal

Germany

Lebanon

Poland

Colombia

Brazil

Belgium

France

Spain

Belarus

Russia

Canada

South Africa

Argentina

U.A.E.

Paraguay

Tunisia

Chile

Norway

Dominican Rep.

Mexico

Peru

Malaysia

Bolivia

+ Show all

– Show less

7-day average

Netherlands

721,429

total cases

Jan. 22

Dec. 22

Sweden

389,439

Czech Republic

646,312

United States

18,284,729

Denmark

140,750

Slovakia

158,905

Switzerland

423,299

U.K.

2,110,314

Israel

382,487

Portugal

378,656

Germany

1,554,920

Lebanon

160,979

Poland

1,226,883

Colombia

1,530,593

Brazil

7,318,821

Belgium

629,109

France

2,490,946

Spain

1,829,903

Belarus

179,196

Russia

2,905,196

Canada

521,509

South Africa

940,212

Argentina

1,555,279

U.A.E.

197,124

Paraguay

101,544

Tunisia

123,323

Chile

589,189

Norway

44,932

Dominican Rep.

161,930

Mexico

1,338,426

Peru

998,475

Malaysia

98,737

Bolivia

151,059

+ Show all

+ Show less

Where new cases are higher but going down

7-day average

Serbia

Jan. 22

Dec. 22

Azerbaijan

Hungary

Turkey

Italy

Romania

Ukraine

Austria

Jordan

Bulgaria

Iran

Greece

Libya

Morocco

Finland

Kazakhstan

+ Show all

– Show less

7-day average

Serbia

307,827

total cases

Jan. 22

Dec. 22

Azerbaijan

205,877

Hungary

308,262

Turkey

2,062,960

Italy

1,977,370

Romania

598,792

Ukraine

1,018,199

Austria

344,357

Jordan

279,892

Bulgaria

194,271

Iran

1,170,743

Greece

132,430

Libya

96,346

Morocco

420,648

Finland

33,717

Kazakhstan

193,503

+ Show all

+ Show less

Where new cases are lower but going up

Countries where new cases are lower had a daily average of less than four new cases per 100,000 people over the past week. The charts, which are all on the same scale, show daily cases per capita and are of countries with at least five million people.

What Is COVID-19?

A coronavirus is a kind of common virus that causes an infection in your nose, sinuses, or upper throat. Most coronaviruses aren’t dangerous.

In early 2020, after a December 2019 outbreak in China, the World Health Organization identified SARS-CoV-2 as a new type of coronavirus. The outbreak quickly spread around the world.

COVID-19 is a disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 that can trigger what doctors call a respiratory tract infection. It can affect your upper respiratory tract (sinuses, nose, and throat) or lower respiratory tract (windpipe and lungs).

It spreads the same way other coronaviruses do, mainly through person-to-person contact. Infections range from mild to deadly.

SARS-CoV-2 is one of seven types of coronavirus, including the ones that cause severe diseases like Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and sudden acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). The other coronaviruses cause most of the colds that affect us during the year but aren’t a serious threat for otherwise healthy people.

Is there more than one strain of SARS-CoV-2?

It’s normal for a virus to change, or mutate, as it infects people. A Chinese study of 103 COVID-19 cases suggests the virus that causes it has done just that. They found two strains, which they named L and S. The S type is older, but the L type was more common in early stages of the outbreak. They think one may cause more cases of the disease than the other, but they’re still working on what it all means.

How long will the coronavirus last?

A day-by-day breakdown

After observing thousands of patients during China’s outbreak earlier this year, hospitals there identified a pattern of symptoms among COVID-19 patients:

- Day 1: Symptoms start off mild. Patients usually experience a fever, followed by a cough. A minority may have had diarrhea or nausea one or two days before this, which could be a sign of a more severe infection.

- Day 3: This is how long it took, on average, before patients in Wenzhou were admitted to the hospital after their symptoms started. A of more than 550 hospitals across China also found that hospitalized patients developed pneumonia on the third day of their illness.

- Day 5: In severe cases, symptoms could start to worsen. Patients may have difficulty breathing, especially if they are older or have a preexisting health condition.

- Day 7: This is how long it took, on average, for some patients in Wuhan to be admitted to the hospital after their symptoms started. Other developed shortness of breath on this day.

- Day 8: By this point, patients with severe cases will have most likely developed shortness of breath, pneumonia, or acute respiratory distress syndrome, an illness that may require intubation. ARDS is often fatal.

- Day 9: Some Wuhan patients developed sepsis, an infection caused by an aggressive immune response, on this day.

- Days 10-11: If patients have worsening symptoms, this is the time in the disease’s progression when they’re likely to be admitted to the ICU. These patients probably have more abdominal pain and appetite loss than patients with milder cases.

- Day 12: In some cases, patients don’t develop ARDS until nearly two weeks after their illness started. One Wuhan study found that it took 12 days, on average, before patients were admitted to the ICU. Recovered patients may see their fevers resolve after 12 days.

- Day 16: Patients may see their coughs resolve on this day, according to a Wuhan study.

- Day 17-21: On average, people in Wuhan either recovered from the virus and were discharged from the hospital or passed away after 2.5 to 3 weeks.

- Day 19: Patients may see their shortness of breath resolve on this day, according to a Wuhan study.

- Day 27: Some patients stay in the hospital for longer. The average stay for Wenzhou patients was 27 days.

Shayanne Gal/Insider

Just because patients leave the hospital, though, doesn’t mean their symptoms are fully gone. Some coronavirus patients report having symptoms for months, including chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, heart palpitations, and loss of taste and smell.

People who got sick and were never hospitalized can have lingering symptoms, too. A July report from CDC researchers found that among nearly 300 symptomatic patients, 35% had not returned to their usual state of health two to three weeks after testing positive. Patients who felt better after a few weeks said their symptoms typically resolved four to eight days after getting tested. Loss of taste and smell usually took the longest to get back to normal, they said: around eight days, on average.

How does the coronavirus spread?

SARS-CoV-2, the virus, mainly spreads from person to person.

Most of the time, it spreads when a sick person coughs or sneezes. They can spray droplets as far as 6 feet away. If you breathe them in or swallow them, the virus can get into your body. Some people who have the virus don’t have symptoms, but they can still spread the virus.

You can also get the virus from touching a surface or object the virus is on, then touching your mouth, nose, or possibly your eyes. Most viruses can live for several hours on a surface that they land on. A study shows that SARS-CoV-2 can last for several hours on various types of surfaces:

Can the virus be ‘reactivated’ after you recover?

In announcing that recovered patients were re-testing positive, South Korea’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) offered a new theory: that the virus could have been “reactivated.”

But experts are more skeptical. Oh Myoung-don, a professor of internal medicine at Seoul National University and a member of the WHO’s Strategic and Technical Advisory Group for Infectious Hazards, says the most plausible explanation is that the tests picked up lingering viral genetic material, rather than reemergent infection.

“Even after the virus is dead, the nucleic acid (RNA) fragments still remain in the cells,” says Oh. He says reactivation of the virus is not as likely.

In South Korea, patients must test negative in two tests within 24 hours before they are released from quarantine.

United States

The number of known coronavirus cases in the United States continues to grow. As of Wednesday morning, at least 18,284,700 people across every state, plus Washington, D.C., and four U.S. territories, have tested positive for the virus, according to a New York Times database, and at least 323,000 patients with the virus have died.

Reported cases in the United States

Average daily cases per 100,000 people in the past week

← Fewer

More →

Ala.AlaskaAriz.Ark.Calif.Colo.Conn.Del.Fla.Ga.HawaiiIdahoIll.Ind.IowaKan.Ky.La.MaineMd.Mass.Mich.Minn.Miss.Mo.Mont.Neb.Nev.N.H.N.J.N.M.N.Y.N.C.N.D.OhioOkla.Ore.Pa.R.I.S.C.S.D.Tenn.TexasUtahVt.Va.Wash.W.Va.Wis.Wyo.P.R.

Sources: Local governments; The Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University; National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China; World Health Organization.

Note: The map shows the share of population with a new reported case over the last week. Sources: State and local health agencies and hospitals.

See our page of maps, charts and tables tracking every coronavirus case in the U.S.

After case numbers fell steadily in April and May, cases in the United States are growing again at about the same rapid pace as when infections were exploding in New York City in late March. But the hotspots are now mainly spread across the southern and western parts of the country.

The New York Times is engaged in an effort to track the details of every reported case in the United States, collecting information from federal, state and local officials around the clock. The numbers in this article are being updated several times a day based on the latest information our journalists are gathering from around the country. The Times has made that data public in hopes of helping researchers and policymakers as they seek to slow the pandemic and prevent future ones.

Read more about the methodology and download county-level data for coronavirus cases in the United States from The New York Times on GitHub.

Are coronaviruses new?

Coronaviruses were first identified in the 1960s. Almost everyone gets a coronavirus infection at least once in their life, most likely as a young child. In the United States, regular coronaviruses are more common in the fall and winter, but anyone can come down with a coronavirus infection at any time.

The symptoms of most coronaviruses are similar to any other upper respiratory infection, including a runny nose, coughing, sore throat, and sometimes a fever. In most cases, you won’t know whether you have a coronavirus or a different cold-causing virus, such as a rhinovirus. You treat this kind of coronavirus infection the same way you treat a cold.

Have there been other serious coronavirus outbreaks?

Coronaviruses have led to two serious outbreaks:

- Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). About 858 people have died from MERS, which first appeared in Saudi Arabia and then in other countries in the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and Europe. In April 2014, the first American was hospitalized for MERS in Indiana, and another case was reported in Florida. Both had just returned from Saudi Arabia. In May 2015, there was an outbreak of MERS in South Korea, which was the largest outbreak outside of the Arabian Peninsula.

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). In 2003, 774 people died from an outbreak. As of 2015, there were no further reports of cases of SARS.

The most concerning symptom: shortness of breath

Once symptoms appear, some early signs should be treated with more caution than others.

«I would of course always ask about shortness of breath before anything, because that’s somebody who has to be immediately helped,» Megan Coffee, an infectious-disease clinician who analyzed the Wenzhou data, told Business Insider.

Patients who develop ARDS may need to be put on a ventilator in ICU. Coffee estimated that one in four hospitalized COVID-19 patients wind up on the ICU track. Those who are ultimately discharged, she added, should expect another month of rest, rehabilitation, and recovery.

But viewing coronavirus infections based on averages can hide the fact that the disease often doesn’t progress in a linear fashion.

«Courses can step by step worsen progressively. They can wax and wane, doing well one day, worse the next,» Coffee said. «An 80-year-old man with medical issues can do quite well. Sometimes a 40-year-old woman with no medical issues doesn’t.»

This story was originally published February 21, 2020. It has been updated over time with additional research findings.

Something is loading.

Cited by 339 articles

-

A Potential Bioelectromagnetic Method to Slow Down the Progression and Prevent the Development of Ultimate Pulmonary Fibrosis by COVID-19.

Masaud SM, Szasz O, Szasz AM, Ejaz H, Anwar RA, Szasz A.

Masaud SM, et al.

Front Immunol. 2020 Dec 4;11:556335. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.556335. eCollection 2020.

Front Immunol. 2020.PMID: 33343561

Free PMC article. -

Applications of Non-invasive Neuromodulation for the Management of Disorders Related to COVID-19.

Baptista AF, Baltar A, Okano AH, Moreira A, Campos ACP, Fernandes AM, Brunoni AR, Badran BW, Tanaka C, de Andrade DC, da Silva Machado DG, Morya E, Trujillo E, Swami JK, Camprodon JA, Monte-Silva K, Sá KN, Nunes I, Goulardins JB, Bikson M, Sudbrack-Oliveira P, de Carvalho P, Duarte-Moreira RJ, Pagano RL, Shinjo SK, Zana Y.

Baptista AF, et al.

Front Neurol. 2020 Nov 25;11:573718. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.573718. eCollection 2020.

Front Neurol. 2020.PMID: 33324324

Free PMC article.Review.

-

COVID-19 Infection and Children: A Comprehensive Review.

Mehrabani S.

Mehrabani S.

Int J Prev Med. 2020 Sep 22;11:157. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_277_20. eCollection 2020.

Int J Prev Med. 2020.PMID: 33312466

Free PMC article.Review.

-

Does Virus-Receptor Interplay Influence Human Coronaviruses Infection Outcome?

Bratosiewicz-Wąsik J, Wąsik TJ.

Bratosiewicz-Wąsik J, et al.

Med Sci Monit. 2020 Dec 13;26:e928572. doi: 10.12659/MSM.928572.

Med Sci Monit. 2020.PMID: 33311429

Free PMC article. -

Immune-boosting role of vitamins D, C, E, zinc, selenium and omega-3 fatty acids: Could they help against COVID-19?

Shakoor H, Feehan J, Al Dhaheri AS, Ali HI, Platat C, Ismail LC, Apostolopoulos V, Stojanovska L.

Shakoor H, et al.

Maturitas. 2021 Jan;143:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.08.003. Epub 2020 Aug 9.

Maturitas. 2021.PMID: 33308613

Free PMC article.Review.